As a filmmaker, entrepreneur, and journalist, I feel I’ve had a lifetime’s worth of fascinating experiences since I’ve graduated from college.

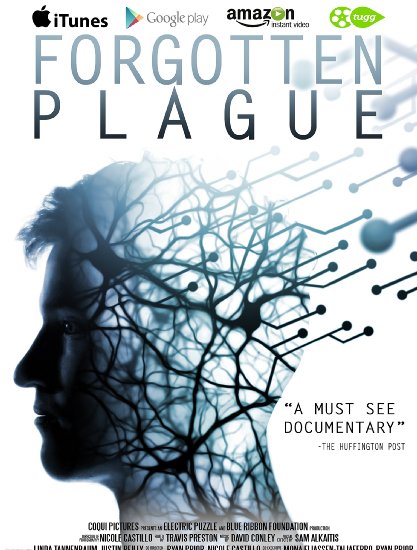

I’ve been invited to speak coast-to-coast from the National Press Club to Stanford Medical School. My film, Forgotten Plague, which tells the story of a disease called myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS) has been hailed a “Must-See Documentary” by The Huffington Post. Each week I might be meeting a U.S. Senator, talking to world-renowned scientists, meeting with CDC officials, or speaking on the radio. But most of what I’m sharing on social media only represents half the story.

Beneath that thin façade of success, there is a much more sinister and grim reality that my team and I live with every day, plagued by the universal notion that there is no magical formula for success other than hustle, 12-14-hour days, and knowing the greatest success in any early business is to fight hard enough so that the organization survives at all. The bad days, of which there are many, are best left forgotten, and the failures are never Instagrammed.

This isn’t out of vanity, but rather a survival instinct.

The only way to get more funding for our film production was to cultivate an image of success and not report to our donors how often we come within a hair’s breadth of failure. Some days it’s the specter of IRS late fees, other days it’s a disastrous contract negotiation, still other days it’s the threat of a global boycott of our film for some perceived slight we committed. I know each week to expect some new challenge that could torpedo our company.

This is the story of perhaps our most dire day: February 21, 2014, when we were filming our documentary in Boston, a thousand miles from home. That day it wasn’t just our film or our company on the line.

My co-director, Nicole Castillo, and I felt like our very lives were in jeopardy.

I’d been experiencing significant chest pain for weeks, and the strain of running a two-person film crew on a hectic national schedule was leaving me gasping for air, barely able to stand, and in so much chest pain that the emergency room was the only solution.

We were leaving to go wait for a taxi in our hotel lobby. “Wait,” Nicole said, heading back into the hotel room. “I need to get something.” She emerged with her camera around her neck. I hadn’t the strength to care that the cold, unblinking lens, which had recorded countless interviews with others, would now be turning its gaze on me.

Nicole filmed nearly every second of our trip to the emergency room. She filmed as I cowered in a chair in the hotel lobby. She was shooting as I leaned against the taxicab window in the fetal position. She was right next to me rolling as I stared into space, shirtless, laying in a hospital bed with electrodes on my chest, while nurses rushed to discover whether or not I was having a heart attack.

My ultimate diagnosis was pericarditis, an inflammation of a sac around the heart caused by herpes viruses and cocksackie viruses. Ostensibly it is caused by a pathogen, but I knew entrepreneurial burnout was the real diagnosis.

My ultimate diagnosis was pericarditis, an inflammation of a sac around the heart caused by herpes viruses and cocksackie viruses. Ostensibly it is caused by a pathogen, but I knew entrepreneurial burnout was the real diagnosis.

My beating heart had swollen to capture and carry the stories of hardship of thousands around the world. Now those horrors threatened to tear me apart not just emotionally, but also physically. The whispering voices of sufferers were a chamber orchestra just off one of my ventricles, beating an off-kilter rhythm you could now hear with a stethoscope.

That episode made the final cut of our documentary, and became one of its most gripping sequences. But what didn’t make it into the film was a scene equally heart-stopping. And yes, I do mean that literally.

Around 2 am, the ER staff concluded I wasn’t dying, and was therefore clear for discharge with some over-the-counter painkillers. I got up from the hospital bed to go find Nicole. A nurse was wheeling Nicole on a bed coming straight toward me. “Odd, yet fun,” I thought, that the nurses must be putting people on wheeled beds and staging races in the halls.

But Nicole’s face was pale, blank. She didn’t return my smile. The nurse docked her in an alcove, half a dozen more staff poured in, and they snatched the curtains shut around them.

“I’m not getting a pulse!” someone shouted.

A few more ran in. I figured someone just hadn’t hooked up the electrodes up correctly. I peaked up over the top of the curtains to try and comfort her with a goofy Bullwinkle grin amid the pandemonium.

She stared blankly, didn’t even recognize me. She was a ghost of her normal self.

I thought to myself, I should be filming this. But Nicole’s camera was still around her neck, blocked by a fierce squadron of ER nurses. This probably wasn’t a great time to grab it.

For several long moments, I watched figures scrambling behind the curtain, until finally, there were faint beeps as her heart rate reached into the zone of 40 beats per minute.

A few minutes later Nicole was cognition, and color. “I’m fine, we need to go home,” she tried to convince them.

“Finding people passed out in the floor of the bathroom isn’t fine,” the nurse retorted. “You were standing and you just hit the deck. We have to keep you for examination.”

Recently, in recounting the story, Nicole told me, “There have only been a few times in my life where I felt, with absolute certainty, that I was dying. That was one of them. As I was lying there, in the bed, I had two thoughts. The first was that I was dying. The second was, ‘Wow, the nurses don’t very good poker faces.’ I was very, very frightened. But I could tell in their faces there were just as frightened.”

Her condition, I learned, was called vasovagal; it is characterized by a sudden drop in heart rate, which leads to fainting. Medical textbooks say it is often caused by a stressful trigger, an example of which might include seeing your best friend admitted to the ER for chest pain in the middle of night, thousands of miles from home, while at the same time you have little to no extra money and no one to turn to.

After, being released from the ER, I fell asleep on a bed outside her room. She wasn’t released until 6 am. We went back to the hotel room, canceled all the shoots for the next day, and slept.

Rattled, and in need of advice, I called my mother, a nurse, and she called her father, a doctor. Remarkably, both advised us to take a day off and continue our trip, the next leg of which included lugging our equipment to a bus station to travel to New York City for a few more days of shooting.

Even more remarkably, we took them up on their advice.

I suppose that simple decision, to board that bus to New York, perfectly encapsulates the other half of entrepreneurship that you don’t always hear about. Even after a harrowing, near-death experience, you take a bit to collect yourself, punch your ticket, and carry on with the next leg of your journey.

The world isn’t there to see your shaky arms thrust the trunk of cinematic lighting equipment into the cargo bay and to mount the steps up into the bus, but those are the moments when you begin to feel you might just be actually earning whatever little success may come your way.

There is, and always will be, only one magical formula. And that is grit.

Recommended Resource: